A relatively small component of the federal tax cuts and Jobs Act passed in December of 2017 was the creation of opportunity zones in every state in the U.S., as well as in the District of Columbia and five U.S. territories.

The purpose of this legislation is to encourage investment in economically distressed communities by making it possible for investors to receive preferential tax treatment.

Tami Bonnell, CEO of EXIT Realty International, explains that individuals who invest in opportunity zones are eligible to reduce taxes on capital gains, depending on how long the investment is held. “If the investment is held for ten years,” she said, “there are zero capital gains taxes on the increase in the investment. It’s a great thing when you can get a return on your investment and invest in people at the same time.”

At a time when bipartisan agreements are rare and becoming rarer, Bonnell points out that the Investing in Opportunities Act was initially supported by Republicans Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina and Representative Pat Tiberi of Ohio and Democrats Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and Representative Ron Kind of Wisconsin.

Opportunity zones have the potential to address many of the country’s most vexing economic problems, Bonnell notes. “One in six Americans lives in an economically distressed community,” said Bonnell. “There is something wrong with the way we’re operating when we have that much poverty in the United States.”

Bonnell cautions that the goals related to opportunity zones need to be closely monitored to insure that both investors and communities benefit. “We don’t want to impose gentrification where people in poverty zones end up with fewer options in smaller and smaller communities,” she said.

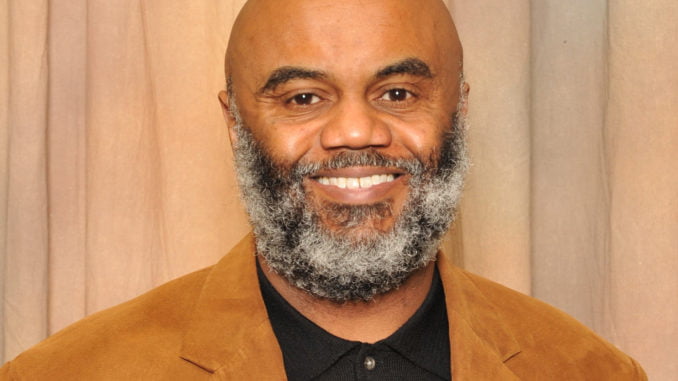

Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, agrees with Bonnell that this legislation has great potential to reinvigorate urban communities, but must be carefully implemented with important “guard rails to insure that it does not become a tool for removal and gentrification.”

“I think what is required,” said Morial, “is for community leaders – mayors, city council members, county commissioners and other local leaders – to legislate conditions that require affordable housing to be an integral component of new projects.”

Morial also wants opportunity zone projects to require that minority and women-owned businesses have a chance to participate in construction and local residents have access to jobs within the zones.

In addition, Morial adds, community leaders – who clearly want these investments – should not wait for Congress to act, but should take the initiative to make certain these protections are in place before projects get under way. “When I look at opportunity zones,” Morial notes, “I see green lights and yellow lights. The yellow lights say caution.”

Moving forward, Bonnell sees one of the biggest challenges associated with opportunity zones is making investors aware of them and how they work. Noting that she travels the country giving dozens of speeches every year, Bonnell often asks audience members to raise their hands if they’re aware of opportunity zones.

“Typically, less than half the audience raise their hands – sometimes it’s just a handful of individuals,” she said. “This is a big opportunity that people are not embracing because they’re not aware of it.”